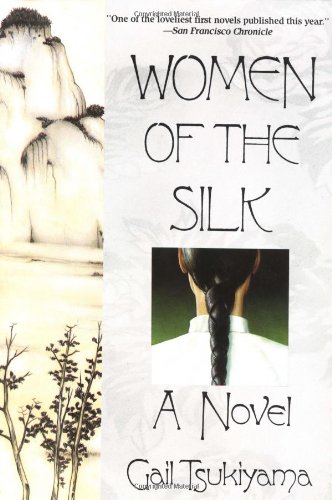

Gail Tsukiyama’s Women of the Silk is, for me, one of those random treasures I picked up during a used book sale in college. Half the fun of these kinds of books is that sometimes they’re terrible, but sometimes they have everything you could possibly ask for in a story and you weren’t even intentionally looking for your perfect story when you picked it up. That’s what this book became for me. I’ll readily admit that it’s pretty much Taylor-bait–Asian culture, story about women, written by a woman, not graphic and depressing like similar books I read in college (except for the end, ugh), and strong bonds between women. It has its flaws, mainly the random head-hopping and too many named characters (it’s hard to keep track of everyone). Then again, the stories of people of color from non-Western nations tend to come across to us as disorganized because we’re not used to that kind of organization (and I’d venture that Tsukiyama is trying to preserve authenticity in that regard).

The story takes place in China in the early 20th century. Pei, a young girl from a poor family, is given away to a girl’s house where she learns how to make silk. Although separating from her family is difficult at first, she quickly finds that going to live at the girl’s house is the best thing that could’ve happened to her. There, she finds freedoms that are denied to most women during that time: the freedom to work and the freedom not to marry. Women in this industry have the option of committing themselves to silk work for life, meaning they don’t marry. When Pei learns that this is an option for her, she knows that it’s exactly what she wants, especially since it would mean she’d never have to leave Lin, a girl with whom she forms a very close bond. However, the Japanese invasion threatens to tear this peaceful life away.

To me, this book is an excellent example of how to incorporate themes like feminism and queerness without hyper focusing on either. Like Christianity and environmentalism, these are themes that can lend themselves to preachiness. They can be forced into a story just for the sake of them being there as opposed to intricately crafted as part of the bigger story.

Feminism Seeps Through; It Doesn’t Flood

The time period in which the book takes place almost automatically invites feminism into the structural foundations of the story. Pei witnesses both traditional places for women, through her mother and sister, and the radical freedoms promised by feminism, of which we’re only given brief glimpses through Chen Ling. Cheng Ling is the one who fully embraces feminism and later leads the revolt against the silk factory manager. Although Pei takes part in this revolt and also follows in Chen Ling’s footsteps of giving herself to silk work, she never has huge internal monologues about it that border on preachy or overly intellectual. Instead, she embraces the heart of feminist/worker’s rights ideology because people she loves have died as a result of not having these freedoms. Thus, her natural reactions to what personally affects her automatically align with feminism. Pei experiences the world a certain way and reacts in the way that she hopes will make her safe. This is how feminism seeps through as opposed to being slapped on just for the sake of getting the message across.

Genuine Queerness

For a book that came out in 1991 and also takes place in 1920s-1930s China, Women of the Silk does a pretty fair job of developing the relationship between Lin and Pei without making the whole story hyperfocus on it and without making it seem to exist for the sake of fanservice. Tsukiyama also doesn’t make the mistake of portraying it as a phase, especially after the events toward the end of the book. While many may take issue with the fact that the relationship never fully blossoms, I think there’s enough story and outside context to justify why that doesn’t happen. Things had to be more on the downlow in the past, but the past also had things like these silk factories and these life commitments to silk work that, at least in this book, seem to serve as socially acceptable marriage ceremonies between women.

Women of the Silk isn’t about feminism and isn’t about being queer, but both of those are parts of the story’s foundation. They don’t come through in long rants or blocks of narration, but rather as a consequence of who each character is as a person and how they experience the world around them. Because these themes are intricately woven into the story instead of slapped onto the surface for the sake of an argument or to seem edgy, they’re actually very strong and make the entire book work well.

When it comes to incorporating strong ideas like these, writers need to build them in from the ground up instead of trying to fit them in after everything is all laid out.

Inspiring post! Somehow it occurs to me Bernice Bing’s art… share with you – http://wp.me/p3bwN9-hp

LikeLike

Hmm, interesting. Thanks for sharing!

LikeLike